|

Author: Erik R. Scott - Professor at the kansas University. Has received Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley. Is author of the book - Familiar Strangers: The Georgian Diaspora and the Evolution of Soviet Empire.

Translators: Salome Berdzenishvili and Anton Vatcharadze.

Editor: Esma Mania.

The article first published in: The Whole World Was Watching: Sport in the Cold War, edited by Robert Edelman and Christopher Young, and published by Stanford University Press.

The article is published with the consent of the author and the publisher.

An official fan guide published for Dinamo Tbilisi in 1960 depicted the stars of Soviet Georgia’s leading soccer team in stylized sketches that showed them singing while engaged in acrobatic leaps toward the ball. The guide’s illustrators knowingly linked Georgian football to the explosive, colorful, and competitive style of male folk dancing that the small republic was famous for throughout the Soviet Union. On one page, Avtandil Ghoghoberidze, the team’s striker, was depicted performing the kartuli—a Georgian wedding dance—with his hands while balancing on the ball. Throughout, the guide implied that the dazzling techniques of Georgian football and the ethnically distinctive movements of Georgian dance were facets of the same national repertoire of body culture. The intimate association of football and dance worked both ways. Around the same time that the guide was published, the Georgian State Dance Ensemble introduced a piece whose playful choreography included passes of a ball made between the dancers.

Sketch depicting Avtandil (Basa) Ghogoberidze

Football was the most popular sport in the USSR, and it reflected and sometimes reinforced social and national divisions in the multiethnic socialist{this word is not typically capitalized in disciplinary usage; please leave uncapitalized unless it will be capitalized throughout entire volume} state. Although the game received government sponsorship, it presented Soviet citizens with a diverse array of competing imagined communities, each with its own symbols, heroes, myths, and grievances. Separate communities formed around Moscow’s strong club teams, the largest rivalry being between Dinamo Moscow, patronized by the secret police and state functionaries, and Spartak Moscow, supported by trade unions and large segments of Moscow’s working class. Successful clubs in the national republics that could take on the center’s leading sides, the most prominent examples being Dinamo Kiev and Dinamo Tbilisi, in effect became national teams supported by large segments of the Ukrainian and Georgian populations.

While club teams throughout the Soviet Union earned praise for skill and effectiveness when victorious, Georgian footballers were known to represent a distinctly ethnic style of play. The Moscow teams had different fan bases but were mainly cheered for winning or castigated for losing. Dinamo Kiev’s style of play was closely linked to Russia; there were many Russians on the team, and their trainer for many years was from Moscow. Similarly, Dinamo Minsk, though less successful than Dinamo Kiev, was difficult to distinguish from a Russian club; many players who failed to make the Moscow teams went to play in Minsk. Ararat Yerevan and Neftianik Baku occasionally upset the Moscow-based teams and were sometimes characterized as displaying a “southern” temperament, but their success was attributed to skill and training, not to the way they played. Georgians seemed to offer a visibly ethnic alternative to the style of play present throughout the Soviet Union.

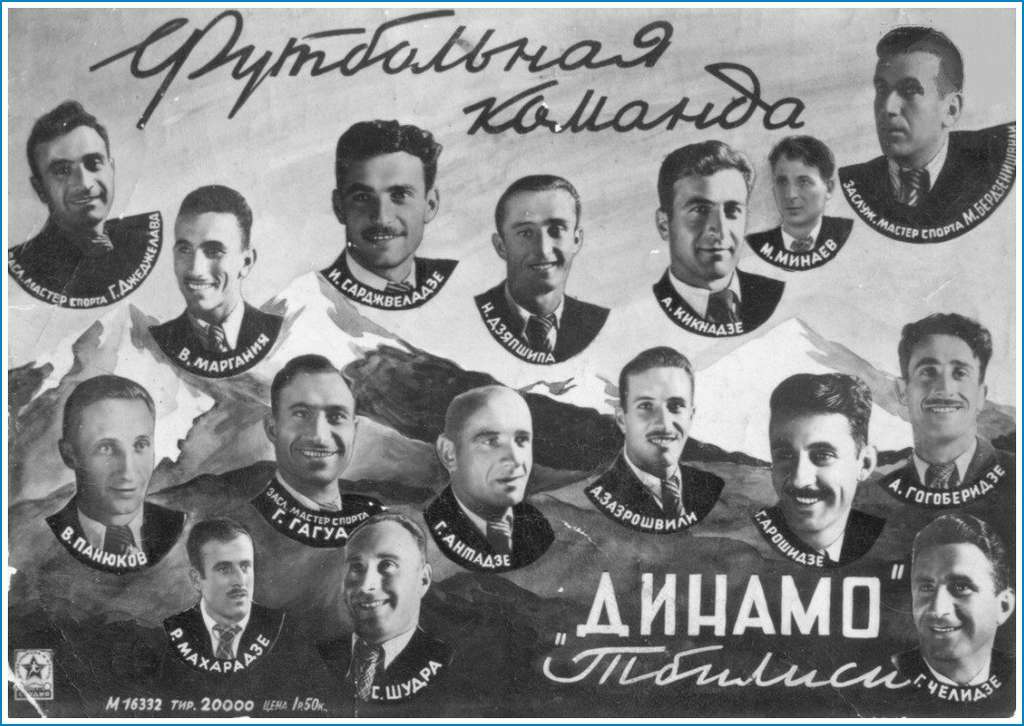

Tbilisi "Dinamo" in the 1940s

The techniques of Georgian football and the mythology surrounding them emerged from the encounter between a centralizing Soviet state and an assertive Georgian republic. The name of Georgia’s most successful team suggested a certain tension: Dinamo was a Pan-Soviet organization run by the police and headquartered in Moscow; Tbilisi was the capital of the Georgian nation and the destination for a massive twentieth-century migration from the Georgian countryside. In Tbilisi, local party leaders supported the establishment of folk troupes that gathered the dances of rural Georgia and choreographed them as recognizable sets of body movements. Meanwhile, the Georgian capital’s leading soccer club assembled the republic’s best players to produce a dominant team that could represent the Georgian nation. Central authorities in Moscow oversaw these developments. They invited Georgian dancers to the Kremlin to showcase the state’s commitment to multiethnic diversity, and they called up Dinamo Tbilisi’s top players to join the sbornaia, the all-Soviet team. Georgia’s dancers and footballers embodied national particularity; policy makers in Moscow sought to ensure that Georgian difference served the needs of an imperial state.

While Georgian football was a hybrid product forged through interactions between periphery and center, it was perceived as a nationally defined alternative to the default way of playing found elsewhere in the USSR. Georgian fans and athletic promoters consciously appealed to its associations with the national style of dance, claiming that it displayed the same qualities of beauty, ingenuity, and agility. Georgian football was also defined by what it was not. Georgian and Russian commentators alike saw it as emotional instead of calculating, dominated by dribbling rather than physical defense, and defined by artistic improvisation instead of brute force. Yet it was still held that Georgian players could form a complementary part of the all-Soviet team.

"Dinamo Tbilisi" - 1948

The mythology surrounding Georgian football was burnished by its imagined connections with the “beautiful game” played by successful South American teams. Interestingly, South American footballers were also held to move on the pitch in ways that evoked dance. The elaborate dribbling of Argentinian football recalled the tango, while the playfulness of Brazilian soccer was associated with the samba. The international successes of Argentina and Brazil’s teams were a source of pride for domestic audiences in the two countries; victories seemed to prove that criolloArgentinian culture and racially mixed Afro-Brazilian culture could succeed against the cultures of larger and more developed countries. Football transformed the cultural qualities associated with South America’s alleged backwardness into assets in a modern and global sport. Local promoters and players often went out of their way to emphasize the ethnic distinctiveness of their team’s style of play, and the gaze of international audiences offered confirmation of these differences.

Soviet Georgia sought similar recognition through football, cultivating a mythology of national distinctiveness on the pitch that, at least for a time, served Georgian and Pan-Soviet purposes. Yet like Argentinians and Brazilians, Georgians also dreamed of a global sense of belonging through soccer that transcended Soviet borders. During the Cold War, Georgian footballers gained a prominent place on the world stage by taking part in the soccer diplomacy that was a crucial component of the Soviet Union’s outreach to the postcolonial world. Just as the United States sought to demonstrate that it had surmounted its racial problems by sending hundreds of African American athletes on overseas goodwill tours, the Soviet Union used soccer to cast itself as a harmonious multiethnic alternative to the United States in postcolonial countries with a past of racially defined foreign domination.

This essay examines Georgian soccer’s twentieth-century evolution and considers how its mythologized embodiment of national difference was used to convey both Georgian nationality and Soviet multiethnicity in the context of the Cold War. It reveals that the Soviet promotion of Georgian soccer had some unintended consequences. On the pitch, Georgian nationality and Soviet multiethnicity took on new meanings that did not always conform to official ideology. Promoted abroad by the Soviet state, Georgian football’s greatest successes were ultimately claimed as evidence of national triumph rather than Soviet achievement.

Like most national myths, the mythology of Georgian soccer emphasized its long-standing pedigree. In truth, Georgia could rightfully claim football as a direct import from Britain rather than a secondhand artifact handed down from Russia. Around the same time that English mill owners introduced soccer to Moscow in the late nineteenth century, English industrialists and workers brought soccer to Georgia via the Black Sea port of Poti. Soccer took hold in Georgia before the Bolsheviks came to power, and observers pointed to a distinctly national style even before the official establishment of Dinamo Tbilisi in 1925. As early as the 1920s, Georgian soccer players were called the “Great Uruguayans” (didi urugvaelebi), a reference both to Uruguay’s dominance in the soccer world and to a supposed southern style of play that valued artistry over athletic discipline and improvised attacks over coordinated effort.

However, Dinamo Tbilisi, which came to stand for Georgian football in general, was forged in the Stalinist period and bore the imprint of Stalin’s Georgian compatriot Lavrentii Beria. This was no coincidence. The All-Union Dinamo Sport Society had been linked to the state’s security and secret police apparatus, the NKVD (People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs), since its founding at the initiative of Feliks Dzerzhinksii. As Georgia’s leading chekist (Soviet secret police officer), Beria played an important role in promoting Dinamo Tbilisi’s early development. The Georgian team, which played its first competitive matches in 1936, considered Beria its “first honorary member.” Dinamo’s stadium in Tbilisi was even named in his honor.

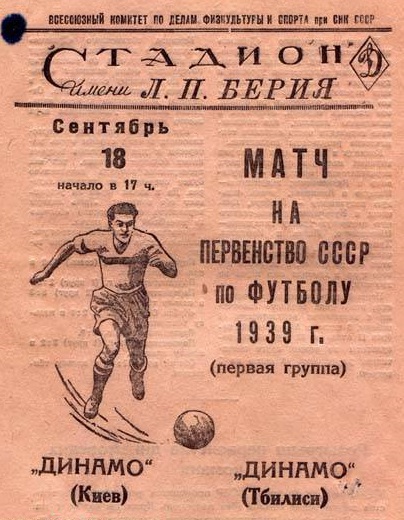

Sometimes, Beria weighed in forcefully to support his club. In 1939, the semifinal match between Spartak Moscow and Dinamo Tbilisi for the Soviet Cup, which Spartak Moscow handily won, was declared invalid and a rematch ordered. According to Spartak player Nikolai Starostin, this decision was made at the “very highest, and no longer athletic” levels of power, quite possibly at the behest of Beria, who continued to serve as the president of the Dinamo sports club even after being promoted to head the NKVD in Moscow. The patronage of Beria, who remained a passionate supporter of Dinamo Tbilisi despite his ascent to the center, was crucial in establishing a lasting institutional basis for soccer in Georgia; he oversaw the development of top-notch facilities and ensured his team a relatively privileged position in the world of Soviet football.

Under Stalin, however, representations of the team’s national distinctiveness tended to adhere to semiofficial ethnic hierarchies. While the “temperamental game” of Georgian footballers was praised for its “highly individualized technical mastery” and “interesting tactical combinations” in a 1949 guide published in Moscow, this exciting, if impulsive, style of play was implicitly contrasted with the hallowed iconography of the Soviet goalkeeper, who stoically stood ready to defend against any attack. In this context, it was significant that Dinamo Tbilisi’s goalkeeper and coach were often Russian. The Georgian side was frequently described as an inconsistent “moody team” in the Soviet press. The pairing of flamboyant Georgian artistry with steely Slavic discipline at the goal line and in the coach’s box may have struck team organizers as a plausible solution to this perceived problem. Such an arrangement was also ideologically appropriate, fitting with Stalinist assertions of the primacy of the Russian people in leading the Soviet Union.

A distinct period in Dinamo Tbilisi’s history came to a close with the death of Stalin and the subsequent imprisonment and execution of Beria by his political rivals in 1953. Despite the incarceration of the team’s patron, Dinamo Tbilisi remained dominant on the pitch that year. On September 4, the team appeared to clinch at least a tie for the Soviet Top League title with a 2–1 victory over Torpedo Moscow. In a turn of events that recalled the role Beria likely played in annulling Spartak Moscow’s victory in 1939, Dinamo Tbilisi’s win was declared invalid. The Soviet press announced that a rematch had been ordered in part because of the “rough play” of two of Dinamo’s players. The speed at which the decision was reached, however, suggested that party leaders deemed it politically undesirable to have the Georgian team claim the title while its patron faced charges of treason. Three days later, a despondent Dinamo Tbilisi lost its rematch with Torpedo Moscow and its share of the title. Georgian fans, regardless of their opinion of Beria, no doubt felt that the central authorities had robbed them of a championship.

Given the team’s close associations with Stalinist authority, Dinamo Tbilisi’s transformation in the wake of Stalin’s death and Beria’s execution was rather astonishing. Although it remained part of the police-sponsored Dinamo organization, the name of the team’s stadium was changed, all references to Beria disappeared from fan guides, and the team in effect went from being a vehicle for Stalinist policies to an embodiment of post-Stalinist ideals of Georgian masculinity. With the disappearance of Georgians from top political posts in the Soviet Union after Stalin, Dinamo Tbilisi’s players became the new heroes for an emergent generation of Georgians, and, in some ways, rooting for the team became a way of expressing nationalist frustrations with the center.

The experience of being a fan also changed in the post-Stalinist period. Fan literature proliferated, Georgian soccer became the subject of popular movies that mythologized its prerevolutionary origins and showcased the extreme devotion of its supporters, and televised matches drew larger audiences, with fans able to watch Dinamo Tbilisi on screens throughout the Soviet Union. Emphasizing the team’s unique artistry, the most famous announcer for Dinamo Tbilisi’s matches was Kote Makharadze, a widely recognized dramatic actor from Georgia whose emphatic expressions, poetic turns of phrase, and heavily accented Russian linked a recognizably Georgian body culture to an audible sound track of readily appreciable difference. When Dinamo Tbilisi finally emerged as the champion of the Soviet Top League for the first time in 1964 (after coming in second in 1939, 1940, 1951, and 1953), the team also gained a new song for its repertoire. Recorded by Orera, a Georgian band that enjoyed Soviet-wide popularity, “chveni orkros bichebi” (Our Golden Boys){the title is in Georgian, which does not have capital letters even when transliterated; the translation of the title should feature capital letters, however, since it is common practice to capitalize titles in English} spoke of “dreams fulfilled” and “goals fulfilled” but made no mention of the Soviet Union or socialism{see note above regarding socialism and the fact that it is not commonly capitalized when referred to as a general ideology}. Set to a guitar and employing traditional Georgian polyphonic harmonies, the song was at once modern and grounded in national culture.

Soviet Union Champions - 1964

Thanks to the efforts of Georgian promoters, whose claims of national uniqueness resonated with Georgian fans, Georgian soccer possessed a unique mythology that fit the skills of Dinamo Tbilisi’s stars. While there were other competitive Georgian clubs that enjoyed passionate local support, such as Torpedo Kutaisi, only Dinamo Tbilisi had a consistent shot at the title and succeeded in winning the Soviet championship. The team stood for Georgian football beyond the borders of the Georgian republic, and its national distinctiveness came into sharper focus when contrasted against the Russian teams it routinely faced. Although the sport was originally a foreign import and had made advances thanks to Stalinist patronage, Dinamo Tbilisi’s success on the soccer field was perceived as part of an innate Georgian artistry.

The Cold War saw the Soviet state mobilize Georgian soccer skills for international audiences, giving Georgian footballers prominence on the all-Soviet sbornaia, which made its Olympic debut in Helsinki in 1952. Two important, if potentially contradictory, criteria shaped the formation of the sbornaia: the team had to reflect the ideal of the USSR as a multiethnic union defined by a fraternal “friendship of the peoples,” and it had to be successful. In the iconography of the “friendship of the peoples,” Russians were typically given the leading role, and the other titular nationalities of the Soviet republics ascribed supporting roles, each with its own distinctive characteristics, which together were meant to constitute a harmonious whole.

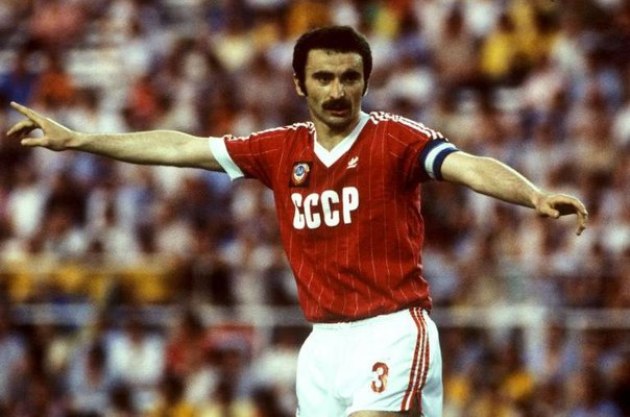

The ideal sbornaia, therefore, might have featured Russians in key positions, with support from a representative selection of non-Russian players drawn from each of the Soviet Union’s fifteen republics (while there are only eleven positions in soccer, one imagines that the smaller republics might have provided substitutes). In reality, the Soviet team that competed in the Olympics and the World Cup looked rather different. Stars from the Moscow-based clubs, along with players from the successful Dinamo Kiev and Dinamo Tbilisi teams, dominated the Soviet sbornaia, reflecting the uneven distribution of success in Soviet football. Even though Georgians made up only 2 percent of the overall Soviet population, they were consistently overrepresented. For the first Soviet Olympic football team, the second-largest contingent of players from a club team came from Dinamo Tbilisi, which provided six footballers. When the Soviet Union made its World Cup debut in 1958, one-fifth of the players on the roster were Georgians from Dinamo Tbilisi, a trend that would continue through the rest of the Soviet period. The first time the Soviet team was captained by a player unaffiliated with a Moscow-based club was in 1972, when Dinamo Tbilisi’s defender Murtaz Khurtsilava took the helm. The second time was in 1980, when the position was assumed by his teammate from Tbilisi, Aleksandre Chivadze.

Soviet authorities often saw the overrepresentation of footballers from the Moscow-based clubs, along with the dominance of players from Dinamo Kiev and Dinamo Tbilisi, as a problem. A report on the performance of the Soviet sbornaia in the 1970 World Cup written by its coach, Gavriil Kachalin, attracted concern with its admission that the “core” of the Soviet team was made up of players from just four Soviet clubs: Spartak Moscow, Dinamo Kiev, Dinamo Tbilisi, and the Moscow-based Tsentral’nyi sportivnyi klub armii (TsSKA). Delegates to the Football Federation of the USSR from republics that rarely supplied players to the Soviet team frequently complained about their lack of representation. Georgian representatives, in contrast, boasted of the success of their southern republic. At the 1970 meeting of the Soviet Football Federation, Tsomaia, the delegate from Georgia, suggested that other republics could learn from the Georgian model: “Maybe we can all carry things out the way we do in our republic. Many of our soccer players play for Soviet youth teams and for the all-Soviet team.” Irritated by Tsomaia’s boasting, Valentin Granatkin, the federation’s chairman, interrupted by exclaiming, “Because you have no winter!”

An even more pressing issue was the Soviet team’s lack of success in international competitions. The Soviet team made it to the semifinals of the World Cup only once, in 1966, where it lost to West Germany, 2–1. While the Soviet press consistently praised the collective team spirit embodied by the sbornaia, and Soviet fans dreamed of finding a harmonious mixture of the disciplined and athletic style attributed to Slavic players and the dexterity and inventiveness associated with Georgians, the team never really coalesced. Some of its problemswere those faced by any national team: it was difficult to coordinate national- and club-level schedules, and there was{I believe it should be kept as “was” based on the structure and significance of the sentence, whose primary meaning is that there was more stability and there was more structure} more stability and structure in club-level organizations. In the Soviet context, however, officials grew concerned that the national team’s shortcomings undermined the state’s ideological message of multiethnic harmony. One alternative pursued by Soviet authorities was to promote the USSR’s more cohesive club teams abroad. Club teams gained some impressive international achievements, with Dinamo Kiev defeating the top teams of Europe to take both the Cup Winners’ Cup and the Super Cup in 1975. Dinamo Kiev’s successes led to a plan to make the Ukrainian club the basis for the Soviet national team. Dinamo Kiev, however, turned out to be a less-than-ideal representation of the Soviet Union. The club’s identity was difficult to separate from that of its coach, Valerii Lobanovskii, who was known for a hyperrational approach to soccer. This reputation may not have been entirely deserved, but it was a popular stereotype associated with the coach and, by extension, his team. Internationally, Lobanovskii seemed to confirm undesirable Cold War–era depictions of the USSR; foreign journalists described him as an emotionless person and derided his players as “Sputniks” and “Russian robots.” It was also nearly impossible for Dinamo Kiev’s players to simultaneously serve the needs of the national and club teams. Shouldering the burden of extra matches and practices, they were overworked and exhausted. The approach ended in 1978, when the Soviet team, formed on the basis of Dinamo Kiev, failed for the first time in history to qualify for the World Cup.

While Dinamo Tbilisi never dominated Soviet football to the same degree as Dinamo Kiev, Georgian difference on the football pitch arguably better served Soviet ideological needs in the Cold War. Unlike their Ukrainian counterparts, Dinamo Tbilisi’s stars were portrayed as colorful and individualistic. As non-Russian and non-Slavic representatives of the Soviet Union, Dinamo Tbilisi’s players were called on to serve as cultural ambassadors to the postcolonial world and dispatched to Latin American countries thought to have an affinity for a similarly southern style of play. Often, they lived up to these expectations. In exhibition matches, they were greeted with cheers in Brazil and Argentina. In 1961, Avtandil Ghoghoberidze was sent to Cuba along with other representatives of Dinamo Tbilisi to meet with Fidel Castro, and photographs show the visiting Georgians posing with Castro after dressing him in a traditional Georgian hat. An even more famous photograph, taken immediately after a 1965 friendly match between the Soviet sbornaia and the Brazilian national team, showed the four Georgian stars of the Soviet team, Anzor Kavazashvili, Mikheil Meskhi, Slava Metreveli, and Giorgi Sichinava, posing arm in arm with a shirtless Pelé, football’s greatest celebrity. The photograph, disseminated widely in the Soviet press, revealed the admiration the Georgians clearly had for the Brazilian football legend but also linked the Soviet team’s Georgian contingent with the idea of a southern style of soccer that could allegedly be found throughout the world.

Pele and Georgian players

In principle, members of Dinamo Tbilisi were meant to evoke Georgian distinctiveness while conveying the cohesiveness of a multiethnic Soviet Union. Sometimes, personal, national, and Pan-Soviet interests coincided: by most accounts, Georgian footballers were initially eager to serve state needs, especially since international travel opened up a world inaccessible to ordinary Soviet citizens. Breathlessly recounting his first visit to Paris in 1954, Ghoghoberidze recalled, “In those years, and even after, an air of magic hung around the words ‘international match.’”

Decades later, the team’s domestic and international successes had bred a greater sense of confidence among Dinamo Tbilisi players and supporters. The team won its second Soviet Top League title in 1979 and bookended this achievement by taking the Soviet Cup in 1976 and 1979. Bringing its distinctive style of play into the international arena, the team sought to claim its place among the top European clubs, which, as Soviet officials and footballers recognized, set the standards by which others were measured around the world. Accordingly, Dinamo Tbilisi’s 3–0 victory over Liverpool in a 1979 European Cup match played before ninety thousand ecstatic supporters in Tbilisi was heralded as a signal achievement. Afterward, Georgian journalists proudly quoted Liverpool manager Bob Paisley’s statement that Dinamo Tbilisi had “pleasantly surprised him” with their level of play.

Dinamo Tbilisi would go on to score the biggest victory in the club’s history, defeating Carl Zeiss Jena to win the 1981 Cup Winners’ Cup. Admittedly, it was less prestigious than the European Cup and played against a fellow socialist club from East Germany rather than a storied Western European competitor. Nevertheless, it was a major coup, both for the Soviet Union, which had a poor record in international football competitions, and for the small nation of Georgia. Soviet authorities and supporters in Georgia both sought to take credit for the victory. Leonid Brezhnev wrote, “It was not in vain that we all rooted for them [Dinamo Tbilisi]” and claimed the victory as one for the entire Soviet Union. Georgians, however, saw the team’s success as a national triumph. Letters and telegrams congratulating the team poured in from Georgians living throughout the Soviet Union, including a woman residing in the Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) who proclaimed, “Henceforth European football will be spoken with a Georgian accent.”

Winner of the 1981 Cup Winners' Cup

The 1981 Cup Winners’ Cup victory seemed to offer an opportunity for Dinamo Tbilisi to transcend the hierarchies of Soviet multiethnicity by superseding their reputation as a “moody team.”{this term is introduced as a direct quote on page 6, footnote 19, and then again in the quote below in this same paragraph} When the club had gained its first Soviet Top League title in 1964, the success of Dinamo Tbilisi’s “golden boys” had been linked to their Russian coach, Gavriil Kachalin. In the judgment of Nikolai Starostin, it was Kachalin who had “skillfully guided this sharp, but not always well-balanced ensemble to victory” by “reinforcing the team’s psychological strength.” However, Dinamo Tbilisi’s 1981 team was successfully managed by a homegrown Georgian coach, Nodar Akhalkatsi. After Dinamo Tbilisi’s Cup Winner’s Cup victory, journalists from Pravda wrote about the team’s temperamental reputation in the past tense: “Earlier Tbilisi Dinamo was often called a moody team, one that could defeat a strong opponent in brilliant style and then, not preparing for their next match, lose to an even worse team.” Now, according to Russian soccer celebrity Valentin Ivanov, the team’s “long-standing skill in improvisation” had finally been “united” with effective organization.

Returning to Georgia, Dinamo Tbilisi’s players were carried off the plane in the arms of supporters and cheered as national heroes as they paraded with their trophy in front of tens of thousands of fans packed into their home stadium. A jubilant song recorded by the Soviet Georgian band Iveria, which blended rock and polyphonic Georgian harmonizing, memorialized the team’s victory. The song’s Georgian-language lyrics left little doubt about the national nature of the team’s achievement. Its narrator praised the “boys” of Dinamo Tbilisi, whose victory had “glorified Georgia”; their success was “like radiant light shining on the mountains and valleys” of the Caucasus nation. This sentiment was echoed by Davit Kipiani, one of the stars of the 1981 squad, who described international matches as a forum for proving the strength and vitality of Georgian national character. Speaking to a fellow Georgian journalist, Kipiani explained, “It’s worth remembering that football is not just composed of feints, dribbling, and passes. Football is also a contest of different character and personality types. And character types, in their essence, are national.”

Dinamo Tbilisi’s success exposed tensions arising from the centralized Soviet state’s reliance on Georgian soccer to achieve its ideological goals. For some Soviet observers outside Georgia, the achievements of Dinamo Tbilisi and the behavior of its fans represented a growing challenge to Russian dominance and Pan-Soviet solidarity. While Georgian players continued to be valued for their contributions to the Soviet team, the victories of Dinamo Tbilisi against opponents from larger Soviet republics was sometimes cause for popular resentment.

Dinamo Tbilisi’s Georgian supporters gained a reputation for pushing and sometimes exceeding the boundaries of acceptable behavior in the multiethnic socialist state. At a 1971 meeting of the Soviet Football Federation, the Georgian representative spoke out against what he saw as a crude depiction of Dinamo Tbilisi supporters as “overly expansive and emotional” in the newspaper Sovetskii sport{Russian capitalization practices differ, and the latter word is not capitalized in Russian}. Meanwhile, Georgian sports officials sought to have a greater say in which players were called up to play for the sbornaia, likely because they wanted to protect the interests of Dinamo Tbilisi. At the same Football Federation meeting the Georgian delegate framed the issue as one of national sovereignty. The delegate explained that the Football Federation had the right to “recommend” players, but to “make demands of the sports committee of a sovereign republic with its own constitution is simply unfair and offensive.”

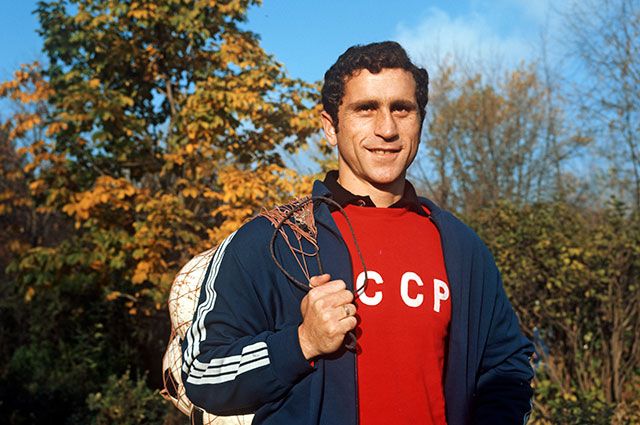

Dinamo Tbilisi’s politically connected patrons in Georgia also asserted local control through the informal use of republic-level institutions. When the team’s top prospect for goalkeeper, Anzor Kavazashvili, sought to leave the club to play in Russia, he was prevented from purchasing a plane ticket and had to depart Georgia in disguise, traveling on a ticket made out in a friend’s name. Tracking him down in Leningrad, representatives from the Georgian KGB came to the apartment where he was staying. Although Georgian authorities relented once Kavazashvili officially began playing in Russia, they used back channels to induce him to return. While playing for Spartak Moscow, Kavazashvili received a call from Givi Chokheli, a footballer from Dinamo Tbilisi who had played with him on the Soviet team. Chokheli, who had been asked by the Georgian sports minister to make a personal appeal to Kavazashvili, asked the goalkeeper, “Don’t you want your parents to live well in their old age?” Kavazashvili was nearly tempted to return to his homeland and his family {added for clarity given quote in preceding sentence}but ultimately refused when he learned he would not be guaranteed the starting spot at goal for Dinamo Tbilisi.

Anzor Kavazashvili

A nagging concern for Dinamo Tbilisi’s supporters was that the team was gaining international recognition as a Soviet rather than a Georgian club. The Georgian national repertoire, which linked an ethnically distinctive style of football to familiar Georgian dances, could be readily recognized by Soviet spectators. However, attempts to use Georgian football to convey the multiethnic diversity of the Soviet state abroad depended on the intelligibility of this repertoire on the international stage. Some foreign observers understood Georgian football as it was intended; a French journalist, for example, described the 1964 Dinamo Tbilisi squad as “the best Eastern representatives of South American football traditions.” Yet the terms of Georgian national difference on the pitch were not always recognized by international observers, and some Georgian supporters grew worried that Soviet sponsorship led foreigners to see the team as Russian. They were particularly irked when publications like the West Ham United newsletter alternately described the victorious 1981 Dinamo Tbilisi team as “the Russians” and “the Soviets,” as if the terms were equivalent. Beyond the Soviet Union, it was common to conflate Russia and the USSR, but because Soviet citizens were categorized by nationality and perceived national distinctions to be significant{I am proposing this edit because I want to emphasize that Soviet citizens lived in a system that officially categorized them by nationality and themselves saw these national distinctions as significant}, Georgian supporters blamed the lack of foreign recognition on the inability of their team—and, by extension, their country—to truly stand alone on the world stage.

In 1990, Dinamo Tbilisi withdrew from the Football Federation of the USSR, and the club was renamed Iberia Tbilisi, a reference to the ancient kingdom of eastern Georgia. Georgian football’s efforts to pursue international success independent of Moscow were linked to the push for national sovereignty. A Georgian journalist writing in the republic’s main newspaper in November 1990 described the Soviet Football Federation as an “imperial structure” that prevented Georgia from “entering the international arena.” Once again linking soccer to dance, the author noted that Georgians had been forced to suffer foreign press accounts that spoke of their republic’s famous dance ensemble as a group of “Russian performers.” Even though the central security organs of the Soviet state had supported and promoted the development of Dinamo Tbilisi, Georgian football became a forum for advancing nationalist separation.

March 30, 1990, the first match of the Georgian Championship. The future president of Georgia, Zviad Gamsakhurdia addresses the audience gathered at "Dinamo" stadium

The failure to field a truly successful all-Soviet team reflected the tensions of the multiethnic Soviet empire{it was not an empire in the formal sense, and it’s common practice in the discipline to use lower-case “e” when referring to empire as a generally concept}, which had grown more apparent in the post-Stalinist period. Putting together a cohesive sbornaia became more difficult as national republics sought to push their own agendas through formal and informal means and central sporting authorities had to coordinate among teams backed by different government ministries. The authorities’ reliance on republic-level teams to represent the Soviet Union abroad generated some expected grievances, since Moscow advanced the prospects of these teams with funding and infrastructural investments but controlled the terms of their international participation and claimed their monetary gains.

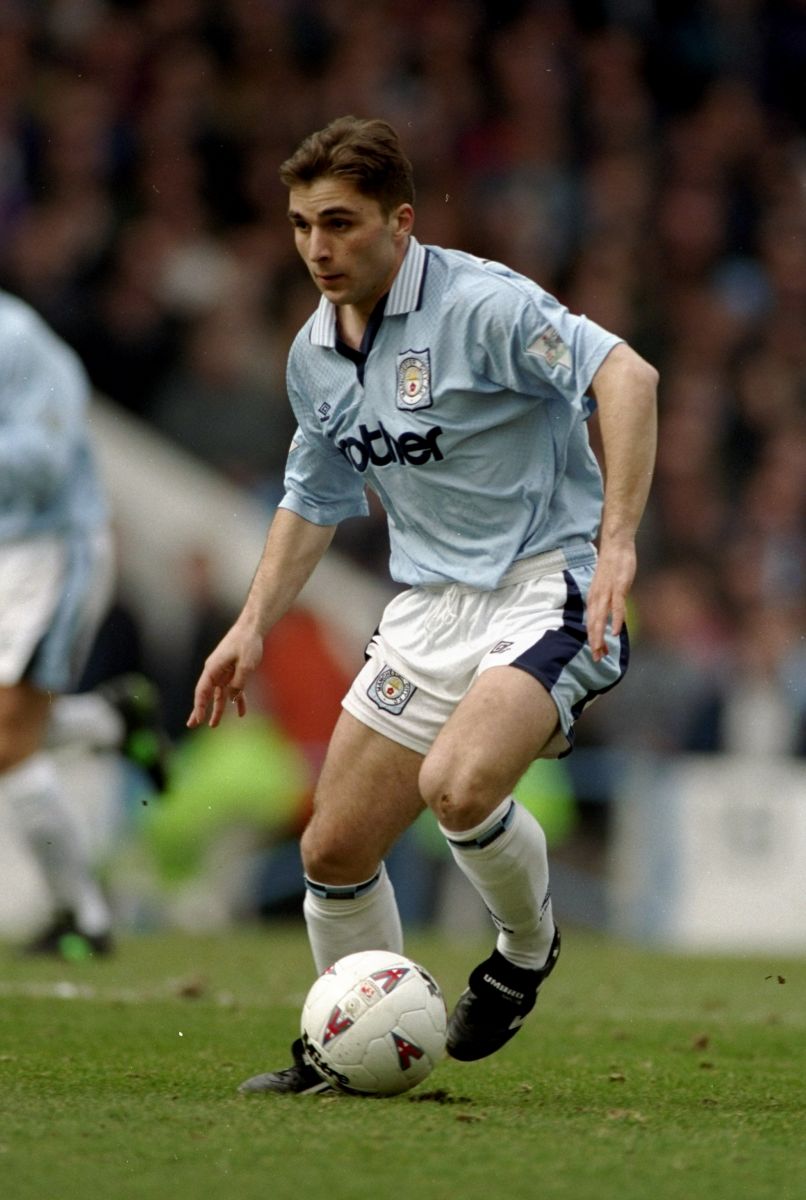

Emboldened by the international prominence they had gained playing for the Soviet Union, Georgian footballers sought more independence and better salaries. Fueled by these ambitions, Georgia established the Soviet Union’s first professional soccer club, Mretebi Tbilisi, in 1988. However, the harsh realities of post-Soviet Georgia made dreams of a South American–style football paradise seem increasingly distant, a development that was wryly observed in the 1991 film I Am Pelé’s Godfather! (me, peles natlia!). In the movie, a middle-aged Georgian man magically travels between a run-down Tbilisi and a sumptuous Brazil full of football legends, scantily clad women, and carnival celebrations. He returns with stories of how he befriended Pelé’s father and taught his son, the Brazilian soccer legend, how to play; however, in Tbilisi his wife is unimpressed, his creditors hound him, and he remains stuck in a low-level job inspecting Georgia’s crumbling electrical infrastructure. In reality, most Georgians with significant football talent left the country; the trends of globalization that accompanied{it is more precise to say that they accompanied the Cold War’s end, since some began before Soviet collapse} the end of the Cold War made transferring to a more prominent foreign team easier and far more lucrative. After living through the Georgian Civil War from 1991 to 1993 and witnessing the collapse of the nation’s economy, Mretebi Tbilisi’s former top prospect, Giorgi Kinkladze, ultimately joined Manchester City for a fee of approximately two million pounds.

Giorgi Kinkladze

While the link between the two was always tenuous, in the post–Cold War era it became increasingly difficult to see soccer as representative of national character. Storied franchises were bought up by foreign investors and the game’s stars purchased by the highest bidder, turning the English Premier League into a global operation in which less than a third of the players were English. Europe’s national teams also grew more diverse, drawing on immigrants and minorities from former colonies; these squads were praised by many for embodying multiculturalism but criticized by others for failing to live up to expectations of national homogeneity. By the early twenty-first century, even the concept of a distinctly Brazilian style of play embodied by Brazil’s national team was more of a myth linked to a successful global brand than a reflection of the team’s actual techniques on the pitch. While Georgians sought to redeploy football as a national institution following the Soviet Union’s collapse, the rules of the game had changed.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sources:

[1] N. Dumbadze, M. Karchava, Z. Bolkvadze, and G. Pirtskhalava, “Dinamo” Tbilisi (Tbilisi: Soiuz zhurnalistov Gruzii, 1960).

[2] Dekada gruzinskogo iskusstva i literatury v Moskve: Sbornik materialov (Tbilisi: Zaria vostoka, 1959), 247.

[3] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1991).

[4] Robert Edelman, “A Small Way of Saying ‘No’: Moscow Working Men, Spartak Soccer, and the Communist Party, 1900–1945,” American Historical Review 107, no. 5 (2002): 1441–1474.

[5] On Dinamo Kiev, see Manfred Zeller, “‘Our Own Internationale,’ 1966: Dynamo Kiev Fans between{not capitalized in original title} Local Identity and Transnational Imagination,” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 12, no. 1 (2011): 53–82.

[6] I am grateful to Robert Edelman{changed to be consistent with other endnote entries} for his observation regarding Dinamo Tbilisi’s name.

[7] On the history of Georgia’s folk-dance ensembles, see Erik R. Scott, Familiar Strangers: The Georgian Diaspora and the Evolution of Soviet Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[8] On the cultivation of football by Soviet and post-Soviet political leaders, see Régis Genté and Nicolas Jallot, Futbol: Le ballon rond de Staline a Poutine, une arme politique(Paris: Allary Éditions, 2018). The book’s authors, French journalists, draw on an earlier, unpublished version of this essay, as well as a podcast interview I gave in 2015, in their discussion of Georgian football. For the interview, see Erik R. Scott, “Georgian Football,” Sport in the Cold War (podcast), episode 8, December 2015, http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/resource/sport-in-the-cold-war/episode-08-georgian-football.

[9] The term “beautiful game” entered international parlance with Brazil’s victory in the 1958 World Cup. Richard Giulianotti, Football: A Sociology of the Global Game (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1999), 26.

[10] Eduardo P. Archetti, Masculinities: Football, Polo, and the Tango in Argentina (Oxford: Berg, 1999); Roger Alan Kittleson, The Country of Football: Soccer and the Making of Modern Brazil (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).

[11] Archetti, Masculinities, 162.

[12] Damion Thomas, “Playing the ‘Race Card’: US Foreign Policy and the Integration of Sports,” in East Plays West: Sport in the Cold War, ed. Stephen Wagg and David L. Andrews (London: Routledge, 2007), 207–221.

[13] Otar Gagua, Boris Paichadze, ed. D. Kvaratskhelia, trans. G. Akopov (Tbilisi: Ganatleba, 1985), 10.

[14] Mindia Mosashvili, maradiuli dghesastsauli [The Eternal Holiday](Tbilisi: khelovneba, 1982), 25.

[15] The term chekist came from a predecessor to the NKVD, the VChK (All-Russian Extraordinary Commission), and continued to be used to refer to those who worked for the NKVD’s successor organizations, including the KGB (Committee for State Security).

[16] Otchety o rabote otdelov TsK KP Gruzii, 1936, sakartvelos shinagan sakmeta saministro arkivi [Archive of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia], Tbilisi, f. 14, op. 8, d. 172; Futbol’naia komanda “Dinamo” Tbilisi (Tbilisi: Izdatel’stvo Gruzpromsoveta, 1940).

[17] Nikolai Starostin, Zvezdy bol’shogo futbola (Moscow: Fizkul’tura i sport, 1969), 68–74.

[18] Nashi futbolisty: Dinamo Tbilisi (Moscow: Fizkul’tura i sport, 1949), 8. On the Soviet goalkeeper, see Mike O’Mahony, Sport in the USSR: Physical Culture—Visual Culture(London: Reaktion, 2006), 140–144.

[19] Gagua, Boris Paichadze, 100.

[20] Sovetskii sport, September 8, 1953.

[21] Drawing on his interview with Aksel’ Vartanian, Robert Edelman advances this argument in Spartak Moscow: A History of the People’s Team in the Worker’s State (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009), 207–209.

[22] The movies referenced arepirveli mertskhali [The First Swallow] (1975) and burti da moedani [Ball and Pitch] (1961).

[23] “chveni okros bichebi!” [“Our Golden Boys!”] YouTube, June 14, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EpUKGOG51KI.

[24] Proekty postanovlenii po voprosam podgotovki sovetskikh sportsmenov k Olimpiade v Khel’sinki, February 21, 1952, Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv sotsial’no-politicheskoi istorii [Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History], (RGASPI), Moscow, f. 17, op. 132, d. 571.

[24] Materialy zasedanii prezidiuma Federatsii futbola SSSR, 1969, Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Rossiisskoi Federatsii [State Archive of the Russian Federation] (GARF), Moscow, f. R-7576, op. 31, d. 296, l. 75.

[25] Materialy zasedanii prezidiuma Federatsii futbola SSSR, 1969, Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Rossiisskoi Federatsii [State Archive of the Russian Federation] (GARF), Moscow, f. R-7576, op. 31, d. 296, l. 75.

[26] See, for example, Stenogramma otchetno-vybornogo plenuma Soveta Federatsii futbola, January 25, 1968, GARF, f. R-9570, op. 4, d. 87, ll. 61–112.

[27] Stenogramma plenuma Soveta Federatsii futbola SSSR, February 4, 1970, GARF, f. R-7576, op. 31, d. 660, ll. 25–51.

[28] Robert Edelman, Serious Fun: A History of Spectator Sports in the USSR (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 136.

[29] Lobanovksii is defended in Hans-Joachim Braun and Nikolaus Katzer, “Training Methods and Soccer Tactics in the Late Soviet Union: Rational Systems of Body and Space,” in Euphoria and Exhaustion: Modern Sport in Soviet Culture and Society, ed. Nikolaus Katzer, Sandra Budy, Alexandra Köhring, and Manfred Zeller (Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag, 2010), 269–294.

[30] Ibid., 283.

[31] Edelman, Serious Fun, 175.

[32] Valentin Bubukin, “Gody letiat bystree miachei,” Sportivnaia zhizn’ Rossii 8 (2005).

[33] Avtandil Gogoberidze, S miachom s trideviat’ zemel’ (Tbilisi: Soiuz zhurnalistov Gruzii, 1965), 142.

[34] Ibid., 48.

[35] Federatsiia sportivnykh zhurnalistov Gruzii, Voskhozhdenie kubku: spravochnik (Tbilisi: TsK KP Gruzii, 1981), 56–57.

[36] Ibid., 104.

[37] Starostin, Zvezdy bol’shogo futbola, 308.

[38] Federatsiia sportivnykh zhurnalistov Gruzii, Voskhozhdenie kubku, 95.

[39] Ibid., 91.

[40] dinamo-dinamo,” YouTube, October 24, 2009, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8lUX37PMw8o {lower-case “d” should be kept as it reflects Georgian usage}

[41] Guram Pandzhikidze, Dinamo, Dinamo, Dinamo!,trans. S. N. Kenkishvili (Rostov-on-Don: SKNTs VSh IuFU, 2011), 55–56.

[42] Stenogramma plenuma Soveta Federatsii futbola SSSR, January 25, 1971, GARF, f. R-7576, op. 31, d. 1013, l. 96.

[43] Ibid., l. 94.

[44] Anzor Kavazashvili, Ispoved’ futbol’nogo maestro (Moscow: Ianus-K, 2010), 35.

[45] Ibid., 49.

[46] Alastair Watt, “Dinamo Tbilisi and the Quest for the Champions League,” Futbolgrad, July 14, 2014, http://futbolgrad.com/dinamo-tbilisi-quest-champions-league.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Edelman, Serious Fun, 241–242

[49] Leonard Shengelaia, “O futbole, i ne tol’ko o nem,” Zaria vostoka,November 28, 1990.

[49] “Kak tbilisskoe ‘Dinamo’ kinulo ‘Mretebi,’” Tribuna, February 27, 2013, http://www.sports.ru/tribuna/blogs/sixflags/427739.html.

[50] “Kak tbilisskoe ‘Dinamo’ kinulo ‘Mretebi,’” Tribuna, February 27, 2013, http://www.sports.ru/tribuna/blogs/sixflags/427739.html.

[51] David Clayton, Everything Under the Blue Moon: The Complete Book of Manchester City FC—and More! (Edinburgh, UK: Mainstream, 2002), 122.

[52] “State of the Game: How UK’s Football Map Has Changed,” BBC News, October 10, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-24464020

[53] See Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff, The Making of Les Bleus: Sport in France, 1958–2010 (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2013).

[54] See Kittleson, The Country of Football, 165–211

___

Publication of this article was financed by the Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI) within the frame of the project - Enhancing Openness of State Archives in Former Soviet Republics and Eastern Bloc Countries. The opinions expressed in this document belong to the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI) and do not reflect the positions of Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI). Therefore, OSI is not responsible for the content.

|