The article is published with the consent of the author and the publisher.

There is a widespread perception that the countries of the former Soviet bloc removed all or most communist era public monuments soon after the end of socialism. Based on a number of heavily publicized instances of iconoclasm, this claim is wildly exaggerated. Focusing on war memorials, the paper provides an overview of cases of destruction and removal, starting in Soviet times. It shows that centralized campaigns to remove Soviet war memorials (as opposed to local initiatives) have been the exception rather than the rule. Thus the most recent Polish decommunization campaign is an outlier among post-socialist policies regarding such memorials. The paper also contextualizes cases of removal and destruction by mentioning other ways of dealing with Soviet war memorials, such as symbolic marginalization, artistic interventions, or new construction.

Even more than Ukraine’s 2014–15 “Leninfall”, the Polish government’s recent campaigns to have Red Army memorials removed has reignited the debate about socialist-era monuments in Eastern Europe. Drawing on a much more detailed forthcoming overview, this brief essay contextualizes the Polish case by focusing on the removal and destruction of Soviet war memorials across national borders.

Is Poland an outlier, or is it simply completing a process started in 1989?

There is a widespread perception that the countries of the former Soviet bloc removed all or most communist-era public monuments soon after the end of socialism. Based on a number of heavily publicized instances of iconoclasm, this claim is in fact wildly exaggerated. It glosses over significant differences between countries and fails to capture the important distinction between the remarkably few centrally orchestrated removal campaigns and the far more frequent but less sweeping instances of monuments removed or modified through local initiative. Most importantly perhaps, it does not distinguish between different types of monuments.

Though sometimes similar in style to other types of statues, war memorials are special because they refer to a complex and contested shared history, and because many of them, even those in central public locations, stand atop war graves. Such memorials are often protected by the Geneva Conventions and a series of bilateral treaties with Russia, Belarus and Ukraine, even though all of these are vague enough to allow for shifting interpretations. Some memorials have been symbolically marginalized without any modification; others, including many in post-Soviet countries, have decayed due to neglect:

Memorial Complex “Immortality”, Moldova (1983). Photo: Lyndon Allin, 2013, with permission.

still others have been objects of politically motivated alterations:

Monument in the village of Stoianiv, Western Ukraine. The word “Soviet” has been chiseled out of the inscription “Your fellow villages are eternally grateful to you who fell for the Soviet fatherland.” A Latin cross has been added, but the red star on the soldier’s helmet remains unchanged. Photo: Mischa Gabowitsch, 2018.

or artistic interventions:

“The Monument to the Soviet Army, Sofia, a day after it had been painted in the colors of the Ukrainian national flag”. Photo: Vassia Atanassova, 2014. Wikipedia Commons.

In addition, a surprising number of new memorials to Red Army soldiers have been built (often but not exclusively in cemeteries) across the former Soviet sphere of influence and as far afield as the United States, Israel, and China. They are often sponsored by state agencies or wealthy donors from Russia or Kazakhstan, but sometimes commissioned and constructed by new immigrants and longtime residents with biographical connections to the former Soviet republics. Along with members of political minorities that sympathize with Soviet or Russian views of the war for a variety of reasons, these groups have also begun using existing memorials as centers of new commemorative rituals for those who fought and died in the war. Whereas such rituals previously tended to follow state-orchestrated choreographies, participants are now developing a range of bottom-up practices emphasizing the commemoration of individuals, even though there is a debate about the extent to which such practices end up buttressing Kremlin-backed geopolitical projects. Examples include the hugely popular processions known as the Immortal Regiment and various secular pilgrimages organized to visit Soviet war memorials in different countries.

Thus, overall, demolition or removal has only been one among many ways of dealing with Soviet war memorials, and hardly the most frequent.

The most spectacular, and most tragic, act of destruction of a Soviet war memorial took place on December 19, 2009, in Georgia. As part of the decentralization of political institutions, a new parliament was going to be built in Kutaisi, then the country’s second-biggest city. To make way for it and as a gesture of symbolic deSovietization, President Mikheil Saakashvili ordered Kutaisi’s Monument of Military Glory to be blown up. The botched detonation sent debris of the 40 meter reinforced steel structure flying hundreds of meters through the air, killing a woman and her eight-year-old daughter and injuring several other people, some of them severely.

Interpreting the monument as a symbol of Soviet occupation was dubious: after all it was a work by two artists from Tbilisi that used motifs from Georgian folklore to commemorate the war dead from the republic. In any case, the top-down decision to destroy it long remained exceptional, though paradoxically there were antecedents from Soviet times.

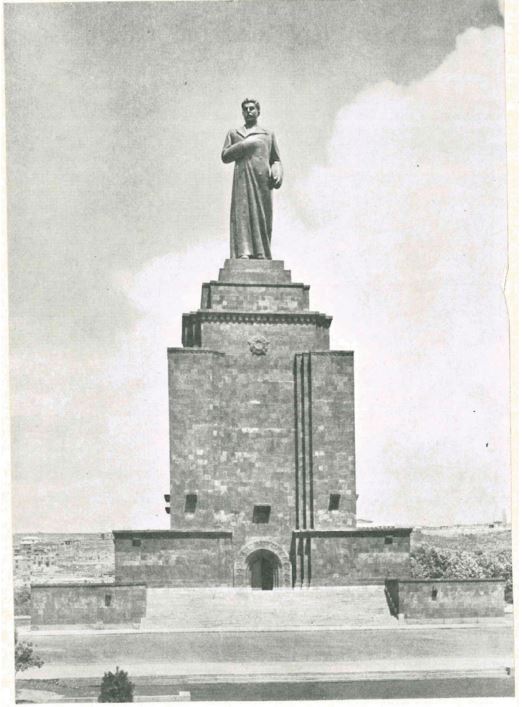

Detonations and demolitions of individual war memorials had taken place in the Soviet Union as early as the 1950s and early 1960s. Until 1953, memorials put up by local residents or individual army units were sometimes destroyed to make way for monuments more closely aligned with official ideology. After Stalin’s death, memorials that commemorated the victory of 1945 in the shape of monumental Stalin statues were singled out for demolition. The victory monument in Erevan, the capital of Armenia, is one example: the 16.5-meter statue gazing towards Turkey from atop a 33-meter pedestal was dismantled in 1962 and later replaced with a statue of Mother Armenia.

Victory Monument (Stalin Statue) in Yerevan (unveiled in 1950, removed in 1962). Source: Iu.S. Iaralov: Monument I.V. Stalina (Moscow: Sovetskii khudozhnik, 1952, cover illustration).

In the 1960s, countless early war memorials – typically simple concrete obelisks lined with granite slabs – were destroyed in order to be replaced with somewhat more elaborate monuments. In addition, there were repeated attacks by individuals – for example in Estonia, Poland and East Germany – on monuments to Soviet soldiers and war memorials that they saw as symbols of Russian occupation.

Since 1989 there have also been spontaneous attacks of this kind and acts of vandalism; yet most war memorials were initially spared from state-orchestrated removal, let alone destruction. Be it in Riga or Lviv, Budapest or Brno: while statues of Lenin or of Feliks Dzerzhinsky, leader of the first Soviet secret police, were often systematically dismantled, there were far fewer removals of war memorials and only occasional instances of complete destruction. Memorials selected for removal were typically statues of individual figures from the pantheon of Soviet war heroes – or else tank monuments.

Poland was a partial exception to this rule. In the post-war years, numerous monuments of gratitude to the Red Army had been erected there in central locations that already served as burial sites. Even as soldiers’ mortal remains were transferred to cemeteries, the monuments often remained at the original sites, and more were built. By 1993, of the nearly 500 monuments of this kind, 130 were removed from public spaces and often replaced with freedom monuments. Crucially, however, this happened through local initiative rather than by directive from Warsaw. Accordingly, Poland saw significant regional and local variation both in policies regarding such monuments and in residents’ attitudes to their removal.

The same goes for most other East and Central European countries. Hungary, often cited as a case of early de-communization of public space, can serve as another example. In 1993, after a controversial debate, Budapest’s municipal General Assembly decided to open a statue park on the outskirts of the city. In addition to other statues from the capital city, this came to house some Red Army monuments, most notably perhaps the Soviet soldier standing at the foot of the Liberty Statue on Gellért Hill. However, the Assembly’s decision only concerned Budapest itself. Even there, the large Red Army Monument on Liberty Square has survived acts of vandalism, calls for removal, and counter-monuments. In the case of the monument to Hungary’s own Red Army (of 1919) in Budapest, a referendum was even held in which residents voted against removal. Outside of the capital, removal was also far from systematic, as evidenced by the Soviet tank monument in Hortobágy in Eastern Hungary.

In Lithuania, most war-related statuary not marking a gravesite did succumb to a wave of spontaneous iconoclasm in 1990–91, but again this was not due to a central government decision. Many statues were eventually relocated to Grūtas Park, opened in 2001. Among other war memorials, they include several statues of Lithuanian partisan Marytė Melnikaitė and of military commanders associated with the period before 1941. In addition, however, it also includes stones removed from Soviet war graves.

Acts of removal have continued throughout the post-socialist period. In most cases these have been initiated by local actors and justified with reference to local circumstances. The typical rationale has been a desire to find a more appropriate site for commemoration. A reverse development has occurred in a number of places in Russia and Belarus, where new monuments have often been erected in the post-Soviet period in more central, easier to reach locations.

The best-known example of a politically motivated conflict was the one surrounding the removal of the Tallinn Bronze Soldier from its original location in the city center to a military cemetery in April 2007. With this decision, the Estonian central government intervened in an existing controversy. The commemorative rituals surrounding Victory Day (9 May) had been growing in popularity as Russian-speaking residents rediscovered the monument as a site of collective self-identification. In response, Estonian nationalists were interpreting it as a symbol of occupation and holding counterdemonstrations in front of it. The government’s attempt to resolve the conflict in technocratic fashion by removing the controversial monument added fuel to the flames, resulting in several days of clashes that left one person dead. In turn, the conflict in Estonia fanned renewed debates about monuments in other countries.

Other types of conflicts arose where monuments had acquired new meanings: as touristic resources, as landmarks for orientation or as improvised skate parks. Thus Legnica, which had housed the headquarters of the Soviet army in Poland, had started using its own central brotherhood monument to market itself as Little Moscow, spurred by the success of a film of the same name – reason enough to resist encroachment from Warsaw. Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, falls in the same category: here those defending the Soviet war memorial included not only embassy officials and left-wing groups, but also skateboarders protective of a space they had appropriated for their own activities.

In Ukraine, the decommunization laws of 2015–16 focused on statues of communist leaders, which were easier to interpret as symbols of occupation than memorials to the fallen of an army in which millions of Ukrainians had fought. War memorials were sometimes reinterpreted and inscribed in new commemorative practices, but they were not dismantled. The few exceptions concerned military commanders who also occupied senior political positions. Even this criterion is far from being unequivocal. In the case of the widely respected Soviet Ukrainian partisan leader Sidor Kovpak, even the law’s authors admitted not having a clear-cut opinion. Conversely, the Kharkiv city administration kept a statue of Marshal Georgy Zhukov off the decommunization list by invoking its artistic value. One monument threatened with demolition at the time of writing is the Military Glory Monument in Lviv, which is dedicated to victory in the war, but also to the post-war Soviet army – it was quite deliberately erected near the outer border of the Soviet Union soon after its armed forces crushed the Prague Spring. However, the removal campaign does not stem from the decommunization laws: it was initiated by local activists, just as its most active opponents are local preservationists and urban historians.

Thus, despite the Ukrainian and other antecedents, when Poland’s national-conservative government launched its campaign in October 2017, it was the first time that a systematic, centrally organized program of removing Soviet war memorials took off in a post-socialist country. An amendment to the 2016 law prohibiting communist propaganda explicitly mentioned gratitude monuments and other war memorials. Exceptions can be made upon application, but the law granted the government-appointed voivodes (governors) and government-affiliated Institute of National Memory wide-ranging interpreting and decision-making powers. While government intervention occasionally meets with creative resistance by local administrations and residents, such countermeasures are not always successful.

Thus the most problematic feature of the Polish government’s campaign is the deliberate decision to ride roughshod over the monuments’ diverse meanings, and wrestle control over public space from local residents by imposing a single top-down interpretation. Indeed, the debate about war memorials is often framed as a conflict between two grand narratives of history, with offended Russian commentators accusing the Polish side of geopolitical affront and attempts to rewrite history. Yet monuments are more than text: over the course of their history they often acquire multi-layered local meanings beyond those intended by their creators or read into them by historians and politicians. This does not necessarily make them less controversial, but it does mean that a controversy about monuments is never simply about who has a correct understanding of history.

___

1 To be published in English in: Lana Lovrenčić, Sandra Križić Roban, Marko Špikić, eds., War, Revolution and Memory: Post-War Monuments in Post-Communist Europe (Zagreb: Institute of Art History), and in German in: Jürgen Danyel, Thomas Drachenberg, Irmgard Zündorf, eds.: Kommunismus unter Denkmalschutz? (Worms: Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft), 49-64.

2 In particular, article 34, paragraph 2b of the Additional Protocol of 1977.

3 The texts of the agreements to which Russia is a signatory can be found on the Russian foreign ministry’s web site; for an overview see: http://mil.ru/commemoration/foreign/agreements.htm.

4 See Mischa Gabowitsch, Cordula Gdaniec, Ekaterina Makhotina, eds., Kriegsgedenken als Event: Der 9. Mai 2015 im postsozialistischen Europa (Paderborn: Schöningh, 2017); Mikhail Gabovich [Mischa Gabowitsch], ed., Pamiatnik i prazdnik (Moscow: NLO, forthcoming).

5 Ewa Ochman, Soviet War Memorials and the Reconstruction of National and Local Identities in Post-communist Poland, Nationalities Papers vol. 38 no. 4, 509–530, 524.

6 Maya Nadkarni, The Death of Socialism and the Afterlife of Its Monuments: Making and Marketing the Past in Budapest’s Statue Park Museum, in: Katharine Hodgkin, Susannah Radstone, eds., Contested Pasts: The Politics of Memory, London: Routledge, 2003, 193–207.

7 Ekaterina Makhotina, Between Heritage and (Identity) Politics: Dealing with the Signs of Communism in Post-Soviet Lithuania. Unpublished manuscript.

8 Karsten Brüggemann and Andres Kasekamp, The Politics of History and the “War of Monuments” in Estonia, in: Nationalities Papers, vol. 26, no. 3, 2008, 425–448.

9 Alexander Astrov, States of Sovereignty: “Nature,” “Emergency,” and “Exception” in the “Bronze Soldier” Crisis, in: Russian Politics & Law, vol. 47, no. 5, 2009, 66–79.

10 See the travel guide: Wojciech Kondusza, Śladami Małej Moskwy (Legnica 2012), 10–12.

11 Daniela Koleva: Pamiatnik sovetskoj armii v Sofii: pervichnoe i vtorichnoe ispol’zovanie (Neprikosnovennyi zapas no. 101, 2015), 184–202, 197.

___

Publication of this article was financed by the Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI) within the frame of the project - Enhancing Openness of State Archives in Former Soviet Republics and Eastern Bloc Countries. The opinions expressed in this document belong to the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI) and do not reflect the positions of Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI). Therefore, OSI is not responsible for the content.

Author: Erik R. Scott - Professor at the kansas University. Has received Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley. Is author of the book - Familiar Strangers: The Georgian Diaspora and the Evolution of Soviet Empire.

Translators: Salome Berdzenishvili and Anton Vatcharadze.

Editor: Esma Mania.

The article first published in: The Whole World Was Watching: Sport in the Cold War, edited by Robert Edelman and Christopher Young, and published by Stanford University Press.

The article is published with the consent of the author and the publisher.