|

Authors: Megi Kartsivadze - Analyst, Archives, Soviet and Memory Studies Direction at the Institute for the Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), MA in Russian Studies, UCL.

Anton Vatcharadze - Head of the Archives, Soviet and Memory Studies Direction at the Institute for the Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), Ph.D. Candidate at the Ilia State University.

General Context[1]

Lenin and Stalin as well as Marx considered that nationalism was a bourgeois concept. They considered that on the one hand, social and economic inequality was revealed through nationalism and on the other hand, bourgeois weaponized it as a “false” ideology for covering counter-revolutionary plans and drawing public attention away from real problems. Moreover, for them, nationalism was an inevitable result of capitalism which should have been overcome through the class conflict. For this, both Lenin and Stalin believed that if they gave an opportunity to ethnic minorities to develop their nationalism, the bourgeoise would lose the control over it and the Soviet government would be able to accelerate the process of overcoming nationalism through the enhancement of class conflict. Also, they considered that the nationalisms of small nations were a response to a chauvinistic character of great powers and in order to prevent such relationship between the Soviet nations, the only form of nationalism which was not supported was the Russian nationalism referred as a ‘great Russian chauvinism’.[2] Such notions and approaches resulted in the policy of korenizatsiia (indigenisation) meaning artificial and targeted development of local, non-Russian ethnic identities.[3]

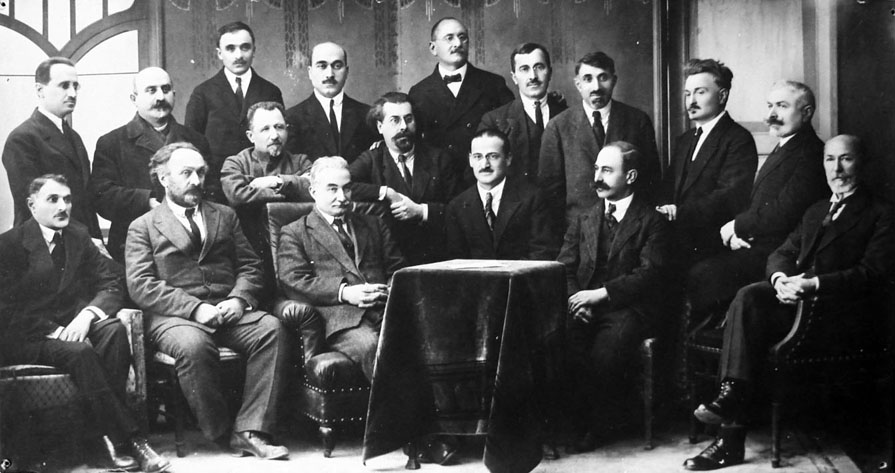

The founder Professor of the Tbilisi State University. In the center – Ivane Javakhishvili. 1918

This policy of korenizatsia also had an impact on the process of national history writing in the Soviet Union. Although the writing of national histories in non-Russian republics was not prohibited, the Marxist-Leninist historical materialism was propagated in the union. Marxist historiography focuses on social class and economy and considers them as major determinants of historical developments. For this, in the Marxist historiography, all historical events are observed through the prism of relations between classes and economy and the classless society is considered as an end of history.[4] Thus, the Soviet historians were expected to write history through the perspective of class analysis. Moreover, the teaching of history at schools was replaced by the interdisciplinary subject of social sciences focused on issues such as class conflict, labour, economy.[5] However, this policy turned out to be unsuccessful for the pre-war mass mobilisation and industrialisation.[6]

In the 1930s, Stalin adopted a new history policy. This included the rehabilitation of Russian history, nationalism and national heroes. First of all, this process served the mobilization of masses and legitimization of Marxist-Leninist ideology in the pre-war period. After the start of the Second World War in 1941, this process became even more accelerated.[7]

In 1934, following Stalin’s order the creation of the standardised textbook of the history of the USSR began. The main function of this textbooks was to incorporate the histories of all of the Soviet nations into one common historical narrative. Several brigades of historians were established, they regularly prepared the drafts versions of the textbook and Stalin was personally involved in their editing.[8] Following lenghty discussions, in 1937, the first official history textbook „Краткий курс истории СССР“ (“Short Course of the History of USSR”) written by Andrei Shestakov was published. However, regardless of the title of the book, it was more of a history of Russia than the history of the other republics.[9] Main problem was that the authours should have found the narrative which would justify the incorporation of the republics first, into the Russian Empire and then into the Soviet Union. All of these should not have any connotation to Russian chauvinism or the Soviet occupation. The history brigades were also created in the non-Russian republics and they were ordered to write the histories of their respective nations.

In the non-Russian republics, the history was being written under the campaign of ‘The Friendship of the Peoples’. This campaign encompassed two central components – 1. At the expanse of ethnic minorities, the Soviet government enhanced the nationalist sentiments of the titular nations of the Soviet Unions;[10] 2. Russian nationalism and culture was considered as a superior to the other ethnicities. The process of history writing was divided into two parts – first, the promotion of primordial view of nationalism, meaning the understanding of the nation as an ancient, natural phenomenon, second, the promotion of Russia’s centrality in the union, meaning that Russia was the nation which should have led the other Soviet nations into Communism with the status of ‘the first among equals’.[11] As a result, the nationalistic sentiments of the non-Russian republics were actively propagated, but the ethnic minorities became a subject to assimilation with the titular ethnicities.[12]

Meanwhile, the state actively supported the celebration of national, exotic characteristics of the nations. For this, periodic weeks of national art were held in Moscow, during which the delegations from Soviet republics visited Moscow and organised exhibitions, literary meetings and various performances. The Georgian delegation went to Moscow in 1937 and presented Georgian literary works, music, dance and arts with great pomp. It was the first time at this event when the epithets such as “Sunny Georgia” were voiced in relation to Georgia. Moreover, it was considered that each titular nation should have its national poet. For which the works of Alexander Pushkin, Shota Rustaveli, Taras Shevchenko and the other national poets of the USSR were translated and propagated throughout the Union.[13] This campaign also influenced the history writing process in the Soviet republics. The history brigades in the non-Russian republics were instructed to write the histories of the respective titular nations from primordial and patriotic perspective while the narrative provided there should have been compatible with the storyline in Shestakov’s textbook.[14] Such commissions were working in all of the Soviet Socialist Republics, and Georgia was not an exception.

History Politics in the Georgian SSR, Ivane Javakhishvili and Stalin

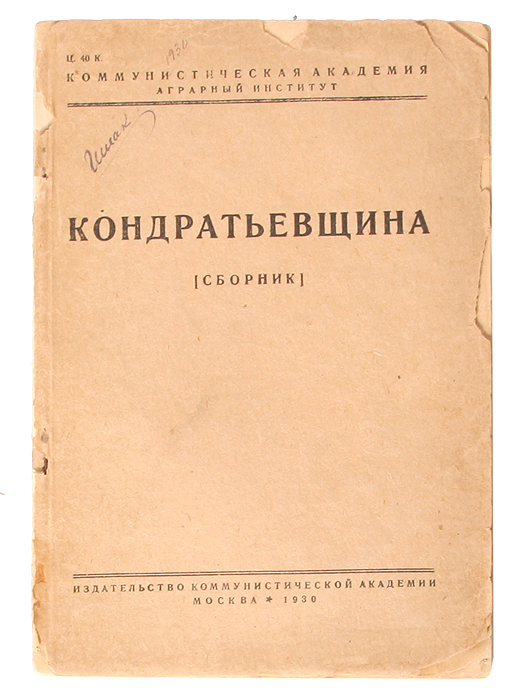

Ivane Javakhishvili as an author of “The History of the Georgian Nation” can be considered as a founder of the Georgian national historiography. Already before the establishment of the USSR, he researched the ethnogenesis of the Georgian people and had important works in this direction. However, after the Soviet occupation, when Marxist historical materialism was actively propagated, his oppression began among the academic circles. In 1926, he was dismissed from the post of Rector of the Tbilisi State University and Tevdore Ghlonti replaced him. In 1928, Ghlonti published an article in the journal ‘sashualo skolisaken’ in which he criticised Javakhishvili and his supporters for not understanding the necessities of a new life. In 1930, the a ‘war’ against non-reliable scientists, also known as kondratievshchina. [15] Within the frame of this policy, in1930, the special meeting was held at the Pedagogy Institute at which the Rector of the institute, Ivane Vashakmadze criticised Javakhishvili and his supporters. His speech was followed by a long discussion among historians, who condemned Javakhishvili’s works. It is notable that Javakhishvili’s former students, Niko Berdzenishvili and Simon Janashia were among his critics and attemted to maintain “balanced” position. Javakhishvili did not attend this meeting. Here are the excerpts of the stenogram of the discussion, which is preserved at the National Archives of Georgia [16]:

Janashia: “The comrade speaker discussed one group among the employees of the Institute and he assigned me to it. I should declare that I highly respect Ivane Javakhishvili and I am thankful to him because he taught me relevant techniques that are necessary for working in science. However, we do not have any common interests. Our public relation is limited to the situation that we have to work at the same institution, the History Department of the Pedagogy Institute”. [17]

Berdzenishvili: “I do not know which group I was assigned to by Professor Vashakmadze. If I am in Javakhishvili’s group, I should declare that my opinion is regretful. I should not be assigned to Javakhishvili’s group […] No, I will read. I was a revolutionary and I plan to be with revolution politically as well as ideologically. I think I am ready for it professionally. As for my attitude toward Prof. Ivane Javakhishvili, I highly respect him as a supervisor especially in the field of history, but it does not constrain me at all from not sharing his ideological concept [from the audience: Down! Down! Down!]”.[18]

Kakabadze: “Let’s take one chapter of this book [Javakhishvili’s “The History of the Georgian Nation”] in which he researches the history of the nation. This book idolizes individual persons. He tells about the kindness of King Alexander and describes his family. … This book encompasses the luxury of kings’ wives and how they spent their times… He writes that someone raped someone’s wife, sorry for mentioning this word. These are the facts upon which Javakhishvili’s history is based. He has written this book with the spirit of Mensheviks”. [19]

Khundadze: “I will tell you about Javakhishvili’s school… It is true that Javakhishvili is a great scientist. He is also a talented man but for now, he is unacceptable. His history is not written with the socialist language… (noice) baric and feudal systems are developed in his book. Then comes capitalism. You will not see facts in Javakhishvili’s research…” [20]

Vashakmadze: “The characterization of Professor Grigol Tsereteli and Javakhishvili are true and all of the speakers characterized them as reactionaries. They did not attend this meeting. One of them declared that he is ill and won’t come out of the door until the meeting finishes, he has neither sent a letter. Also, he did not sign in the process aimed against Poland in 1929. This proves that he is a representative of old feudalism. Hoe can he bring up the new cadres for socialist rebuilding? Javakhishvili can’t. Many came out and said that they respect Javakhishvili but do not have methodological connections with him. This declaration proves the existence of political fraction. The lecturers who support Javakhishvili’s methodology and schools are characterized by his methodology. We should throw them into the 17th century”. [21]

These quotes show that Javakhishvili became a subject of criticism because his works on the history of Georgia did not fit the Marxist principles. While the historians were required to write history from the perspective of class analysis, Ivane Javakhishvili’s works did not satisfy this requirement and for this, an image of enemy was being actively created out of him. This process did not finish in 1930 but became even worse in the following years. In 1931, he was dismissed from the university. Although he was restored to the position in 1933, in 1936 the attach on him was renewed.

On 23 March 1936, a four-day discussion was held at the History Faculty. Karlo Oragvelidze, Rector of the Tbilisi State University, accused Javakhishvili of justifying feudalism, bourgeoisie and nationalist sentiments. After this, the “discussion” continued among historian, most of whom condemned Ivane Javakhishvili. For creating an impression about these meetings, we provide some quotes from the speeches of attendants:

Tsintsadze: “Javakhishvili wrapped in Menshevism, nationalism tries to prove the unity of the Georgian people in terms of resistance without intenral class conflict… He tries to explain this by bringing cultural re-building from Europe and not Russia. Why he looks toward Europe and not Russia can be easily explained, because we know that the Mensheviks considered Russia as an enemy and escaped from its proletarian dictatorship and the Bolshevik party. Motivated by this, Pofessor Javakhishvili attemts to have links with Europe and represent Georgia as historically completely separated from Russia. It would not be unnecessary to mention that his Menshevist conception derives from his nationalist-bourgeois character, wanting to throw the majority of the society into the abyss through anti-Leninist notions”. [22]

Berdzenishvili: “The author of the ‘History of the Georgian Nation’ [Ivane Javakhishvili] is definitely a highly qualified historian in terms of technical expertise. […] Of course, today we approach the historical facts and events discovered by him critically and according to the Marxist-Leninist historical principles we will approve some of them and reject or revalue the others. We will also make new discoveries there where he did not notice them. […] It can be said without any exaggeration that Professor Ivane Javakhishvili significantly advanced the Georgian historiography but it is also an undisputed fact that he did not manage to take the Georgian historiography out of this shameful backwardness”. [23]

Niko Berdzenishvili

Jinjvelashvili: “Regardless of the numerous works written by Javakhishvili on the history of Georgia, he did not provide a true history of class conflict. He has researched the history of kings without exception, their adventures, wars in details but the main facilitator of history, class conflict, which characterizes the history of the people settled on the Georgian territory is forgotten”. [24]

Janashia: “I agree with the general opinion about Javakhishvili provided in the speech. It would be funny to prove that Javakhishvili is not a Marxist, neither he assures nor anybody beleves that he is a Marxist. The thing is that we should teach the youngsters how to approach Javakhishvili. […] We always tell the audience and teach, based on the relevant materials, how to approach Javakhishvili, what to accept from his works, what to reject and how to accept. It is unnecessary to talk about Javakhishvili’s great achievements. It is enough to list his works or just look at the shelves in the library where Javakhishvili’s books are allocated in order to understand how much effort this person has put in his works. […] It is not right to say that Javakhishvili’s only achievement is the collection of facts. He also has some general notions that we can accept. It is not right in two ways: first, it creates a false impression that all of the facts that are collected by Javakhishvili are true and we should accept them as Javakhishvili represents them; second, it creates an illusion that from now on there is nothing left to do with the facts”. [25]

Simon Janashia next to the final-year students of the Tbilisi State University

Janelidze: “I think that main purpose of this discussion is to reveal the bourgeois-nationalist character of Javakhishvili’s school, its flaws for creating Leninist history. Of course, we cannot entrust this work to bourgeois-nationalist professors. Ivani Javakhishvili’s work did not give us a true history of Georgia which is concerned with class conflict after the fall of patrimonial system […] The main reason for this is that Ivane Javakhishvili devotedly and consistently followed the same path his class was chasing. He became the representative of the ruling class. Although this ruling class gave many revolutionary historians to proletariat but Professor Javakhishvili is not among them. He has stayed faithful to his class until now”. [26]

After this discussion, Ivane Javakhishvili left the university. His situation is perfectly revealed in his letter sent to Varlam Dundua by him in 1936:

‘Dear Mr Varlam,

I sincerely thank you for the books that you have purchased for me. I would be thankful if you could find some other books for me as well, especially Latyshev’s et Caucasica, which was printed at the Classical division of Archaeological Society, and Borwn’s research, published in the proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of Russia. Also, can one find the geographical works of Greek and Latin historians at the second-hand booksellers […]? Let me know the price. I need to buy them as I have to return the university books in this short period of time and it will be diffuclt for me to work without them. Now I should tell you a reason why I have to think about purchasing these books. A war against me at the Tbilisi State University has been renewed. K. Orgavelidze read a three-hour report […] in which he attempted to prove the uselessness of my works because they are not Marxist, which is not a discovery for anyone. This was followed by a four-day ‘discussion’ at which the Pro-Rector Gr. Janelidze made a spiteful speech... and some of my former students also stepped forward. […] I have decided that from now on, my staying at the university would insult my self-esteem and for this reason I have given a statement to the Commissar of Education that I am leaving the university, I have suspended the publication of my works and I should start working on a different speciality. I also have to return all the books to the university. My silence and the above-mentioned request are caused by this. Thank you for your attention and help. I am sorry for disturbing you and wish you long, happy and productive life.

Forever your Iv. Javakhishvili.

All of our peers are fine. As for me, you can easily guess my situation”. [27]

However, shortly after these events, the attitude of the Soviet government toward Javakhishvili has changed radically. In 1936, he became a head of the History Department of the Nationa Museum of Georgia, science-consultant of the Research Institute of Caucasian Studies, and in 1939, he was elected as a member of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Also, together with Niko Berdzenishvili and Simon Janashia, he started working on the first official history textbook of Georgia. The first version of the textbook “History of Georgia from Ancient Timed until the Beginning of XIX Century” was prepared in 1940, but it was only published in 1943, after the death of Ivane Javakhishvili. In 1945, Berdzenishvili and Janashia met Stalin in Sochi, about which we learn from Berdzenishvili’s memoirs. They received instructions directly from him on the necessary changes in the textbook and the final version was published in 1946. This textbook won Stalin’s Prize.

Some historians explain this radical change in the attitudes of the Soviet government by the hypothesis that the reports about Ivane Javakhishvili reached Stalin. Involved in the ‘war’ against ‘Trotskyists’, Stalin wanted to prove that he was not from a wild but cultural country, for which Ivane Javakhishvili’s works were useful. Therefore, according to these historians, Stalin ordered to suspend oppressions against Javakhishvili. Such explanation of the changed attitudes toward Ivane Javakhishvili is not based on any tangible document or fact and it is more of an interpretation of events. Considering the general context in Stalin’s Soviet Union, it is much easier to explain why the Soviet government changed its policy toward Javakhishvili.

Under Stalin’s history politics, during this period, new history textbooks were being written in the whole Soviet Union and the common, unifying narrative was being created. This narrative, on the one hand, was Russo-centric and represented the incorporation of different nation into the Russian-led unity as a positive, progressive event and, on the other hand, it was primordial and served the substantiation of the anciency of the Soviet titular nations. In the case of Georgia, the assertion of the links between Georgians and the people of Western Asia was the main objective of the historians. Ivane Javakhishvili’s works on the ethnogenesis of Georgians had an important function in this process. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Soviet government decided to get him involved in the writing of the new history. If we observe the shifts in the historical narrative and compare Javakhishvili’s “The History of the Georgian Nation”, textbooks of 1940, 1943 and 1946 co-authored by Javakhishvili, Berdzenishvili, Janashia, with one another, it becomes obvious that in the final edition, Javakhishvili’s works are used, factual materials but they are interpreted in a way which, on the hand, does not contradict the principles of Marxist historiography and, on the other hand, is compatible with Stalinist historiography. Since this period, the concepts such as “Russia- the lesser evil”, “Through Russia to Europe”, etc. have appeared in the Georgian historiography. Therefore, it can be concluded that the change in the Soviet officials’ attitude was facilitated not by Stalin’s sentiments toward his homeland but by simply pragmatic motif to create the new historical narrative, compatible with the common Soviet historical narrative, on the basis of Javakhishvili’s works and their novel interpretation.

Apparently, the idea, voiced by Niko Berdzenishvili at the “discussion” in 1936, to rethink the invaluable facts discovered by Ivane Javakhishvili in a new, “critical” way and asses them according to the “Marxist-Leninist historical method” turned out to be the most acceptable for the Soviet government. Ivane Javakhishvili survived the repression and returned to historical work but his works were still impacted by the Soviet history politics and for years, they had been interpreted in the new way. Although he survived Stalin’s terror, Ivane Javakhishvili’s fate was still tragic because until the end of his days, he did not have an opportunity to work independently, following his ideas and values in which he believed.

Also, it should be noted that regardless of their “devotion” to Soviet ideals express during the “discussions” in 1930 and 1936, many critics of Ivane Javakhishvili became the victims of Stalin’s terror. Among them were Ivane Vashakmadze who was sentenced to death in 1937, accused of “Trotskyism” [28] and Karlo Oragvelidze who was accused of establishing “right-wing-Trotskyist” organization at the Tbilisi University and leading it on Malakia Toroshelidze’s order [29]. [29] A small conflict of interest with the Soviet authority was enough for the system to sacrifice anyone who was “useless” for it.

Moreover, it is significant that considering Soviet context, the speeches of Berdzenishvili, Janashia and some other historians in 1936 were not easy and required bravery. In the times when the system actively propagated the Soviet people to be “Pavlik Morozovs” [30], it was the hardest task for historians to still call Javakhishvili their teacher and assess him in a balanced manner.

___________________________________________________________________________

[1] Based on: Megi Kartsivadze, Stalin’s Cult in Georgian Colors: The Development of the First Official History Textbook of Georgia and the Emergence of Georgian Stalinism (unpublished MA dissertation, University College London, 2019), pp. 15-19.

[2] Vladimir Lenin, O Natsional’nom Voprose i Natsional’noi Politike [On Nationality Question and

Nationality Policy], Moscow: Polizdat, 1989; Joseph Stalin, ‘Marksizm i Natsionalnii Vopros’ [‘Marxism and

the National Question’] in Stalin I.V. Sochineniia [Works of J.V. Stalin], II, Moscow: Polizdat, 1946, pp.

290-367.

[3] George Liber, ‘Korenizatsiia: Restructuring Soviet Nationality Policy in the 1920s’, Ethnic and Racial

Studies, 14, 1991, 1, pp. 15-23

[4] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology, Moscow: Progress, 1976.

[5] Sergei Alymov, ‘Ethnography, Marxism, and Soviet Ideology’ in Roland Cvetkovski and Alexis

Hofmeister (eds.), An Empire of Others: Making Ethnographic Knowledge in Imperial Russia and the USSR,

Budapest: Central European University Press, 2014, pp. 121-144.

[6] David Brandenberger, National Bolshevism: Stalinist Mass Culture and the Formation of Modern Russian

National Identity, Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 2002 (შემდეგში:

Brandenberger, National Bolshevism), pp. 27-42.

[7] David Brandenberger, ‘The Search for a Usable Party History’ in Propaganda State in Crisis, New Haven

and London: Yale University Press, 2011, pp. 25-50.

[8] Brandenberger, National Bolshevism, pp. 45-55.

[9] Andrei V. Sestakov, Kratkii Kurs Istorii SSSR [Short Course on the History of the USSR], Moscow:

Polizdat, 1937.

[10] Titular nations refer to dominant ethnic groups in particular Soviet republics: Georgians in Georgia, Armenians in Armenia, etc.

[11] Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939,

Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2001 (შემდეგში: Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire), p.

451.

[12] Gerhard Simon, Nationalism and Policy Toward the Nationalities in the Soviet Union, Boulder, San

Francisco, Oxford: Westview Press, 1991, pp. 135-172.

[13] Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire, p. 439.

[14] Brandenberger, National Bolshevism, pp. 123-131.

[15]Nikolay Komdratives was a Russian economis who was arrested in 1930, accused of membership of the non-existent Party of Workers and Peasents. He was sentenced 8 years in prison in inhumane conditions. In prison, he continued working on research which was then published in several books. In 1938 he was shot.

[16] The stenograms of the 1930 and 1936 discussions and Ivane Javakhishvili’s personal letters are also available in the book by Vakhtang Guruli.

[17] National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N476, d. N1, v. N1, c. N1, p. N29

[18]National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N476, d. N1, v. N1, c. N1, pp. N214-216

[19]National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N476, d. N1, v. N1, c. N1, pp. N56-57

[20]National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N476, d. N1, v. N1, c. N1, p. N70

[21]National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N476, d. N1, v. N1, c. N1, p. N311

[22]National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N471, d. N19, v. N1, c. N1, pp. N14-15 (Discussion on the Situation on Historical Front-line)

[23]National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N471, d. N19, v. N1, c. N1, pp. N44-45 (Discussion on the Situation on Historical Front-line)

[24]National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N471, d. N19, v. N1, c. N1, p. N83 (Discussion on the Situation on Historical Front-line)

[25]National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N471, d. N19, v. N1, c. N1, pp. N117-118 (Discussion on the Situation on Historical Front-line)

[26]National Archive of Georgia, Central Archive of the Recent History, f. N471, d. N19, v. N1, c. N1, p. N164 (Discussion on the Situation on Historical Front-line)

[27] Vakhtang Guruli’s book.

[28] Ivane Vashakmadze in Stalin’s lists - http://www.nplg.gov.ge/gwdict/index.php?a=term&d=26&t=1944

[29] Karlo Oragvelidze in Stalin’s lists - http://www.nplg.gov.ge/gwdict/index.php?a=term&d=26&t=8866

[30]Pavlik Morozov (1918-1932) – Russian child who denounced his family members and then gave testimony to the court against them, for which, according to official version, he was killed by his father’s relatives.

___

Publication of this article was financed by the Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI) within the frame of the project - Enhancing Openness of State Archives in Former Soviet Republics and Eastern Bloc Countries. The opinions expressed in this document belong to the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI) and do not reflect the positions of Open Society Institute Budapest Foundation (OSI). Therefore, OSI is not responsible for the content.

The article will be added soon in English

The article will be added soon in English

|